I’ll be honest. I knew little about Sarajevo before we arrived.

Most of what I knew? I saw on TV in third grade. That’s when images of people sprinting from crackling gunfire, in a faraway land called Bosnia, took over the news shows I sometimes watched with my mom.

It was the first war I remember. And the first to get personal, when our class got a new student. He’d fled Bosnia with his family to Jacksonville, where he lived just a few miles from me. We played tennis together but never really talked about his former life. I can’t imagine what he must have gone through.

This is where my thoughts were as our bus ambled through the bucolic Bosnian countryside. Overcast skies greeted us as we descended to Sarajevo’s base, smack dab in the middle of a valley bearing her name.

It’s this geography, we’d later learn, that made Sarajevo a perfect host for the 1984 Winter Olympics. The five mountains surrounding her are a skier’s paradise.

They’re also what made her a perfect target. From April 1992 to February 1996, Serbian forces besieged Sarajevo, firing 329 rounds on average into the city. Per day.

They’re also what made her a perfect target. From April 1992 to February 1996, Serbian forces besieged Sarajevo, firing 329 rounds on average into the city. Per day.

This lasted three years. An estimated 11,500 people were killed, including more than 1,500 children. Over 50,000 were wounded.

It’s the longest siege of a capital in modern history.

And not just any capital. Sarajevo had successfully hosted the Olympics just eight years prior, showing that a small communist nation could shine on a global stage if given the chance. She’d been an epicenter of culture and arts; a place where different religious and ethnic groups co-existed in a state resembling peace.

How did this happen?

It started with a breakup.

The breakup was Yugoslavia’s, in the late 1980s. This was the communist federation once comprising modern-day Bosnia & Herzegovina, Croatia, Slovenia, Macedonia, Serbia, Montenegro, and Kosovo.

Like Slovenia and Croatia, Bosnia soon voted for independence in a nationwide referendum. Hers was held after theirs, in February 1992.

But, unlike the other two nations, Bosnia was (and is) very diverse. At the time of the referendum, about half of her population was Bosniak Muslim, 25% was Orthodox Serb, 6% was Catholic Croat, and 13% identified as “Yugoslav.”

Bosnian Serbs, however, refused to recognize the vote. They allied with the Serbian government, who, under convicted war criminal Slobodan Milošević and the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA), led the charge to gain Bosnian territory where ethnic Serbs lived.

That charge led to unspeakable horror for thousands. The majority of those who died or suffered were Bosnian Muslims, targeted in a campaign of “ethnic cleansing.”

Such “cleansing” really meant the erasure of everything people held dear: their homes and mosques, their livelihoods and families. Their lives.

The scale is unspeakable. Its effects permeate Sarajevo: their presence seen not just in pockmarked buildings and mass gravesites, but in the glass-and-concrete high rises too shiny to have been there for long. Their newness reminds the world that Sarajevo is strong, and she’ll rebuild.

But she’ll never forget.

Who was Sarajevo before the war engulfed her? Before the world stood by and watched her burn?

She was a trade hub for the Ottomans, who founded Sarajevo in 1461. Along with building a mosque, marketplace, public bath and other structures, the Ottomans invited Sephardic Jews exiled from Spain to resettle in their dazzling new city, which furthered its growth in the 1500s.

The Ottomans also built a foundation of strong hospitality, making Sarajevo a popular stop en route to Mecca. (Such hospitality still persists. Our hotel receptionist, who planned several of our daytime excursions and switched our room free of charge, was one example. So were the many servers who advised us on what and what not to order).

We visited a historic example of Ottoman hospitality at Morića, a “han” (free lodge) built in 1551 by governor Gazi Husrev-Beg. While it no longer offers free room and board for a night, the current owner donates a portion of profits to youth-in-need. (So you can feel good about ordering a Bosnian coffee there a time or two, as we did.)

A Hapsburg raid and fire in 1697 left Sarajevo in shambles, until the mid-1800s. In 1878, Austria-Hungary snatched the city from the defeated Ottomans, per terms of a treaty with multiple European parties.

A Hapsburg raid and fire in 1697 left Sarajevo in shambles, until the mid-1800s. In 1878, Austria-Hungary snatched the city from the defeated Ottomans, per terms of a treaty with multiple European parties.

Her new owners polished her up with trams and other trappings of modern European capitals. This lent to the blend of architectural styles (Islamic & Viennese) you still see.

Soon, Sarajevo became more than a spiffed-up city. She became the place that launched the war. It was on the northern end of the Latin Bridge that Gavrilo Princip, a 20 year old Serb nationalist, shot and killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife Sophie as they rode by in a carriage.

A quick refresher from history class: Austria-Hungary retaliated, which led to the domino effect of war declarations between European powers. Which led to WWI.

A quick refresher from history class: Austria-Hungary retaliated, which led to the domino effect of war declarations between European powers. Which led to WWI.

Sarajevo declined in importance once Yugoslavia formed in 1918. During WWII, the Croatian Ustase (Fascists) took her over, slaughtering her Serbs, Jews, and Romani. (Over a hundred Muslim citizens signed a resolution condemning the actions).

After WWII, Sarajevo once again became a beacon of modernity. Insofar, at least, as that was possible for socialist nations.

But her landing of the 1984 Olympics, over Sweden and Japan, speaks to her stature. She was the first socialist city to host the Games. To date, she’s the first city with a mostly Muslim population to do so too.

One snowy morning, we visit remnants of these Games: Sarajevo’s bobsleigh and luge track. To get there, we take the Sarajevo-Mount Trebević gondola. Reopened this April, it navigates over what was a ghost town after the war. Today’s panoramas are stunning, revealing revitalization and redevelopment.

The track is a stunner too. Built for the ’84 Games, it became an artillery position for Serb forces during the war. (It’s something of an art project now, though apparently limited renovations are underway).

“They still say Sarajevo had the greatest Winter Olympics ever,” says Kitty, our free walking tour guide with Meet Bosnia Travel. She’s the one who tells us to visit the track when we can.

“They still say Sarajevo had the greatest Winter Olympics ever,” says Kitty, our free walking tour guide with Meet Bosnia Travel. She’s the one who tells us to visit the track when we can.

We’re a group of seven: understandably small, considering the chill and wind. Kitty braves the conditions with a seemingly-permanent smile. This makes her a perfect subject for the photographer accompanying us: he’s been hired to take marketing shots. (So don’t be surprised to see our faces if you ever google “Bosnia” and “tours”).

Kitty also has a natural enthusiasm that suits her work. “Sarajevo is like the Jerusalem of Europe,” she says, wildly gesticulating toward the historic mosque, cathedral and temple she shows us. All are within a kilometer of each other, and most are within Baščaršija, the cultural and historical city center.

Sightseeing is great. But the best way to experience Sarajevo’s multiculturalism? Is to taste it.

“Did you know we have our own baklava?” Kitty exclaims. We all stop to buy some from the gentleman below, who makes a secret version called “Zhandar” that takes two days prep time.

Each of those days is worth it. This stuff is delicious. It’s slightly-less-sweet version of what you’re used to, featuring walnuts (and, occasionally, hazelnuts).

Burek is another staple with Turkish and Slavic roots that you can find in many takeaway joints. The round version, which consists of pastry crusted filled with cheese, spinach, and/or meat, was allegedly developed in a Serbian town. The Bosnian version also has an added layer of dough on top. As well as an optional sour cream topping…for added health benefits, I presume.

But Sarajevo, at its culinary core? Is all about ćevapi. You find it on nearly every menu.

Looks like someone shoved breakfast links into a pita, doesn’t it? Not too exciting.

Looks like someone shoved breakfast links into a pita, doesn’t it? Not too exciting.

But there are actually two types of beef meat, hand-mixed, in these sausages. And the “pita” is a tasty, soft flatbread (lepinje). Often, it’s filled with chopped onions, sour cream, feta cheese and other goodies as well, making ćevapi a “try-at-least-once” kind of dish (even for red meat avoiders like us).

Sarajevo does believe in vegetables: zucchini, peppers, and eggplant, to name a few. Most of these are served stuffed or grilled. We sampled some at Kibe Mahala, along with lamb (spit-roasted a few feet from your table), stuffed cabbage rolls, and klepe (meat-filled pasta in sour cream and garlic sauce).

We enjoyed our three-hour meal in the company of new friends, who’d invited us to join them after the walking tour. It’s perhaps fitting that, between the five of us, we hailed from so many places: Iran, the U.S., Spain, and Peru.

(And that we came together to celebrate Sarajevo’s diversity in it’s most delicious form.)

Sarajevo’s diversity had so clearly been its strength. And continues to be.

Where else do you see a skyline shared by minarets and steeples? Or hear cathedral bolls toll alongside the call of the muezzin?

Where else can you sip Turkish tea while eating a slice of Viennese cream cake? One spot is just off the square in Baščaršija. (From here, you can also watch people feed pigeons, to the point where birds climb on their heads. This is a mindblowingly popular activity).

You can pass a pleasant time in Sarajevo just wandering around, eating and drinking. It’s tranquilly beautiful that way.

You can pass a pleasant time in Sarajevo just wandering around, eating and drinking. It’s tranquilly beautiful that way.

But you can’t visit Sarajevo without reckoning with the recent past.

But you can’t visit Sarajevo without reckoning with the recent past.

The city doesn’t try to hide it: along with the shell-shocked buildings, there are museums and numerous “war tours” for visitors.

We opted for the former, starting with the War Childhood Museum. It’s based on the book War Childhood: Sarajevo 1992–1995, a collection of 1,000 short memories of the conflict by author and curator Jasminko Halilovic.

Its setup is like that of Zagreb’s Museum of Broken Relationships. But in this case, the objects were donated by someone who’d grown up during the war.

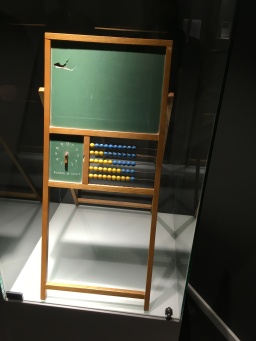

Many stories and objects have to do with loss: of parents, siblings, friends, teachers. But just as many are about resilience. Take this chalkboard, cracked by a mortar shell. It was submitted as proof of its owner’s persistence in her studies. (Classes were held underground during the war, in any space that could be had). Another submitted her favorite book: one that offered her fantasy, and escapism, from a terrible situation.  Greg and I spent time listening to video testimonies too. These were anecdotes about the war from people who are now our age. People talking about life in a place where the loss of teachers, classmates, friends and family wasn’t uncommon; where “duck and cover” in the classroom wasn’t a drill.

Greg and I spent time listening to video testimonies too. These were anecdotes about the war from people who are now our age. People talking about life in a place where the loss of teachers, classmates, friends and family wasn’t uncommon; where “duck and cover” in the classroom wasn’t a drill.

To listen to these stories was to understand our privilege. We’d never had to worry if we’d make it school alive, or if our parents would survive their commute. We’d never clung so hard to education, and to books, as a means of sheer survival.

Those feelings multiplied at the The Crimes Against Humanity and Genocide Museum. Here, the war’s impact is laid bare. Photographs of beatings and executions line the walls, next to images of mass graves of Bosnian Muslims. Some are still being exhumed.

Hanging next to photos of dead children is a poster of bolded statistics: 5-15 people shot per day by snipers, 100,000 damaged homes; half a million missiles fired. This was life in Sarajevo. For three unimaginable years.

Humanity’s capability for terror is inexplicable. So is our capacity to let it happen.

“The tragedy of Srebrenica will forever haunt the history of the United Nations,” said UN Secretary General Kofi Annan in 2000.

In one of its last rooms, the museum highlights the slaughter at Srebrenica. Declared a “safe zone” for Bosnian Muslims by the UN Security Council, the town was populated by UN Peacekeeping Forces, who withdrew as the Serb army approached in 1995.

Over three days, the Serbs systematically separated the men and boys from their families in Srebrenica. And then executed 8,000 of them.

The scale of it. The shame of it. How did people survive in Sarajevo, with this as their backdrop?

They did what people do in crises. They improvised: growing vegetables wherever they could carve out gardens, using plastic covers to shield windows at night so snipers couldn’t get a clear shot. They did the same with garbage bags in tram windows as they commuted.

And they built a massive tunnel, which served as the only safe way in and out of the city.

On our last morning in Sarajevo, we visited the Tunnel Museum,. This houses a remaining section of the Tunnel of Hope.

Built under the Sarajevo airport runway, the tunnel was the only way humanitarian aid, military supplies and other goods could flow into the city.

People flowed too: 3,000 to 4,000 of them per day passed through the tunnel. Judging from the tight space, and the frequent flooding, it wasn’t a pleasant journey.

But for so many people, it was a lifesaving one.

Today, life is vibrant in Sarajevo. She rebuilds. She renews.

But she’s not immune to her past, and its threat to her future.

In 1995, leaders from Bosnia, Serbia, Croatia, the U.S. and Europe, signed the Dayton Peace Agreement in Dayton, Ohio, effectively ending the war. (Signatories included Serbian leader Slobodan Milošević, who died in prison in 2006 following a war crimes conviction.)

Dayton outlined what is probably the most complex federal power-sharing system ever devised. Bosnia was split into three political federations: the north and west Republika Srpska (mostly Serb), the east and central Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (mostly Bosnian), and Brko (a tiny, multiethnic area).

The Federal presidency rotates between Bosnians, Serbs and Croatians for one 8 month term. The three presidency members are elected by the people: one member elected from the Serb contingent of Republika Srpska, and two by the Bosnians and Croats.

You can see how such a system could spell disaster. Dayton was only meant as a stopgap, after all; not a permanent state. Indeed, tension simmers between Bosnia’s various ethno-religious groups today. One only hopes the newly elected President, an avowed Serb nationalist, upholds his promise to stick by what was agreed to in Dayton.

To see Sarajevo is to see humanity at its strongest, while understanding it at its worst.

It’s to see the imprint of empires, and peaceful (and delicious) co-existence of cultures.

It’s also to wonder what will happen next. The effects of war are lasting.

So are those of smoking. Almost a quarter million Bosnians are expected to die from tobacco-related illnesses in the next twenty years.

A campaign is underway to stop this. Yet smoking persists everywhere: every restaurant, every bar, no matter how high end.

I can’t help but wonder if this too is part of the past- the fact that cigarettes were the only real currency during the war.

But how much of the past is the future here remains to be seen. For now, the present in Sarajevo is serene. And she’s a city not to be missed.

You’ve made me want to visit Sarajevo. I think going to more off the beaten track places is the way to go in these days of increasing tourist numbers.

LikeLike

I’m so glad, and you should! It’s such a fascinating city, and I think it was one of our favorite experiences largely because it wasn’t overrun with visitors. And we really didn’t even get to see that much of the city- it’s huge!

LikeLike